On this excerpt from Unleashing the Energy of CSS, we take a deep dive into how you can choose parts with the CSS :has() selector.

Heralded as “the dad or mum selector”, the :has() pseudo-class has far better vary than simply styling a component’s ancestor. With its availability in Safari 15.4+ and Chromium 105+, and behind a flag in Firefox, it’s a good time so that you can change into acquainted with :has() and its use instances.

As a pseudo-class, the essential performance of :has() is to type the factor it’s hooked up to — in any other case referred to as the “goal” factor. That is much like different pseudo-classes like :hover or :lively, the place a:hover is meant to type the <a> factor in an lively state.

Nonetheless, :has() can be much like :is(), :the place(), and :not(), in that it accepts a a listing of relative selectors inside its parentheses. This enables :has() to create advanced standards to check towards, making it a really highly effective selector.

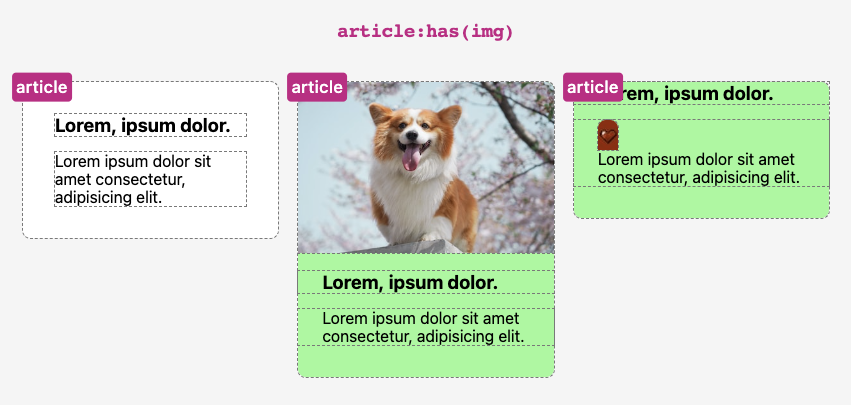

To get a really feel for the way :has() works, let’s have a look at an instance of how you can apply it. Within the following selector, we’re testing if an <article> factor has an <img> factor as a baby:

article:has(img) {}

A doable results of this selector is proven within the picture under. Three article parts are proven, two containing photos and each having a palegreen background and completely different padding from the one with out a picture.

The selector above will apply so long as an <img> factor exists wherever with the <article> factor — whether or not as a direct baby or as a descendant of different nested parts.

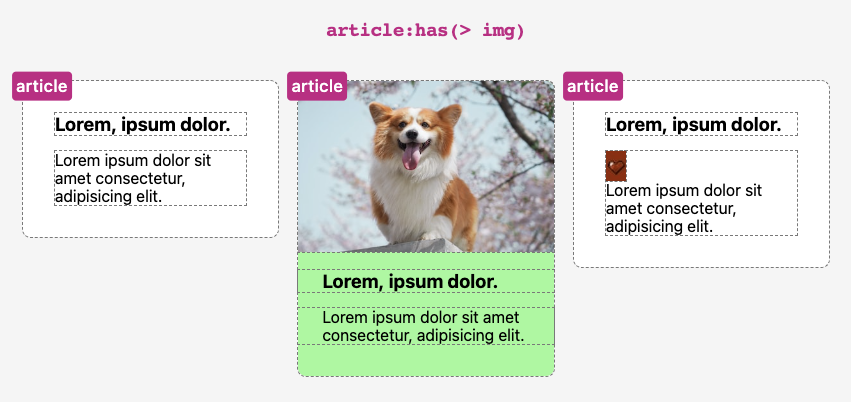

If we need to ensure the rule applies provided that the <img> is a direct (un-nested) baby of the <article> factor, we will additionally embody the kid combinator:

article:has(> img) {}

The results of this variation is proven within the picture under. The identical three playing cards are proven, however this time solely the one the place the picture is a direct baby of the <article> has the palegreen background and padding.

In each selectors, the kinds we outline are utilized to the goal factor, which is the <article>. This is the reason of us usually name :has() the “dad or mum” selector: if sure parts exist in a sure means, their “dad or mum” receives the assigned kinds.

Be aware: the :has() pseudo-class itself doesn’t add any specificity weight to the selector. Like :is() and :not(), the specificity of :has() is the same as the best specificity selector within the selector record. For instance, :has(#id, p, .class) may have the specificity afforded to an id. For a refresher on specificity, assessment the part on specificity in CSS Grasp, third Version.

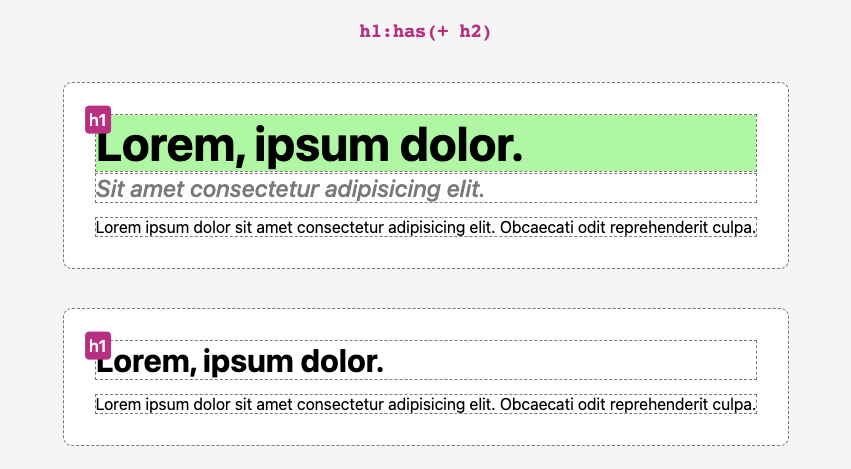

We will additionally choose a goal factor if it’s adopted by a selected sibling factor utilizing the adjoining sibling combinator (+). Within the following instance, we’re choosing an <h1> factor provided that it’s immediately adopted by an <h2>:

h1:has(+ h2) {}

Within the picture under, two <article> parts are proven. Within the first one, as a result of the <h1> is adopted by an <h2>, the <h1> has a palegreen background utilized to it.

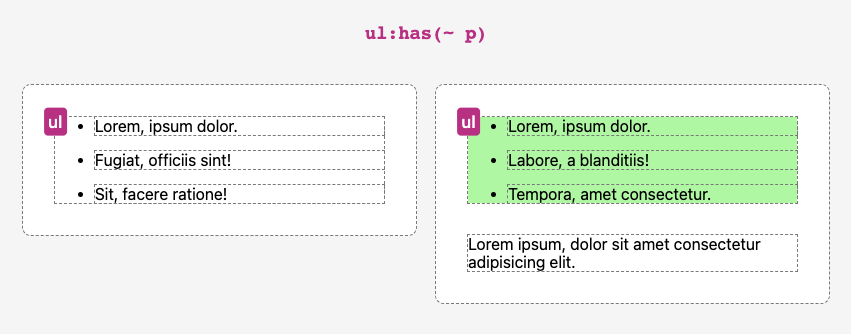

Utilizing the final sibling combinator (~), we will verify if a selected factor is a sibling wherever following the goal. Right here, we’re checking if there’s a <p> factor someplace as a sibling of the <ul>:

ul:has(~ p) {}

The picture under reveals two <article> parts, every containing an unordered record. The second article’s record is adopted by a paragraph, so it has a palegreen background utilized.

The selectors we’ve used up to now have styled the goal factor hooked up to :has(), such because the <ul> in ul:has(~ p). Simply as with common selectors, our :has() selectors will be prolonged to be much more advanced, corresponding to setting styling situations for parts indirectly hooked up to the :has() selector.

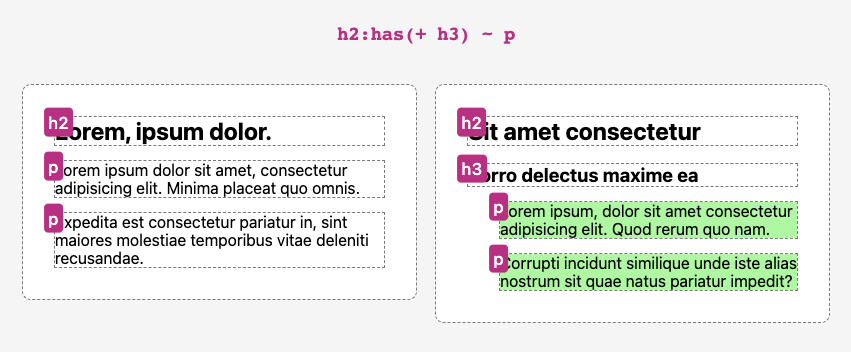

Within the following selector, the kinds apply to any <p> parts which can be siblings of an <h2> that itself has an <h3> as an adjoining sibling:

h2:has(+ h3) ~ p

Within the picture under, two <article> parts are proven. Within the second, the paragraphs are styled with a palegreen background and an elevated left margin, as a result of the paragraphs are siblings of an <h2> adopted by an <h3>.

Be aware: we’ll be extra profitable utilizing :has() if now we have understanding of the accessible CSS selectors. MDN gives a concise overview of selectors, and I’ve written a two-part collection on selectors with further sensible examples.

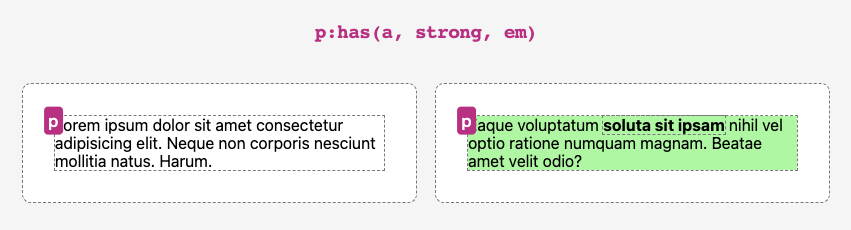

Bear in mind, :has() can settle for a listing of selectors, which we will consider as OR situations. Let’s choose a paragraph if it contains <a> _or_ <sturdy> _or_ <em>:

p:has(a, sturdy, em) {}

Within the picture under, there are two paragraphs. As a result of the second paragraph accommodates a <sturdy> factor, it has a palegreen background.

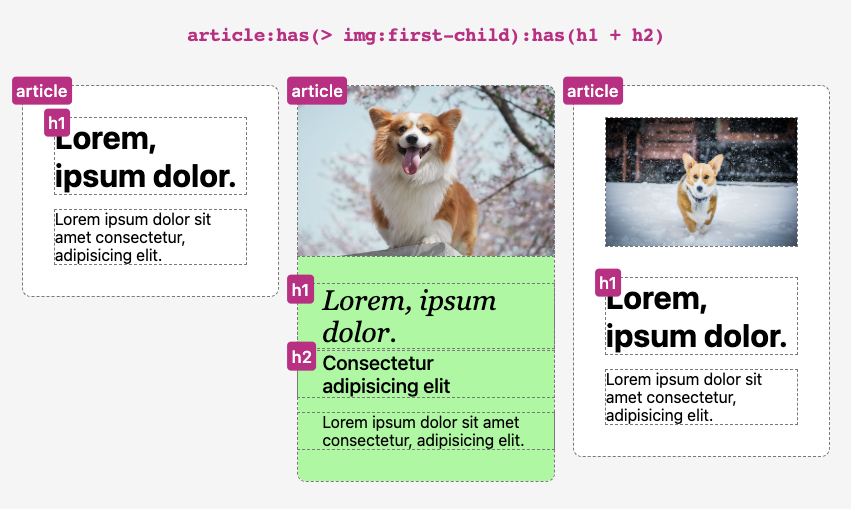

We will additionally chain :has() selectors to create AND situations. Within the following compound selector, we’re testing each that an <img> is the primary baby of the <article>, and that the <article> accommodates an <h1> adopted by an <h2>:

article:has(> img:first-child):has(h1 + h2) {}

The picture under reveals three <article> parts. The second article has a palegreen background (together with different styling) as a result of it accommodates each a picture as a primary baby and an <h1> adopted by an <h2>.

You’ll be able to assessment all of those fundamental selector examples within the following CodePen demo.

See the Pen

:has() selector syntax examples by SitePoint (@SitePoint)

on CodePen.

This text is excerpted from Unleashing the Energy of CSS: Superior Methods for Responsive Person Interfaces, accessible on SitePoint Premium.